|

|

| A bone player in swallow-tail

coat and fancy dress shirt, ca.1860. The attire shown here is typical of the costuming used for the minstrel show's first

part. | Oh!

Susanna, Dixie, The Camptown Races, Buffalo Gals, and Jim Crack Corn are but a few of the very popular songs known from the

minstrel era. When a plantation owner had a man with musical talent, he might send him to New Orleans or up north to be trained

in violin so he could play Celtic music for the cotillions and parties. But, when that man was alone in his quarters, he would

pour his African soul into his Irish fiddle. This was the music the "black faced" minstrels tried to copy.

Minstrel music was established in the late 1830s

with the development of the five-string banjo by Joel Sweeney of Appomattox Court House, Virginia. This new form of music

became very popular as the performers, working usually in pairs, toured from town to town or traveled with the circus. In

1843, Dan Emmetts "Virginia Minstrels" performed the first minstrel show with banjo, fiddle, bones, and tambourine. From this

point, "minstrel mania" swept the nation as hundreds of minstrel troupes toured throughout the country. It reached its peak

in the 1850s and 1860s as it became the popular music of the people. It ran on New Yorks Broadway for over forty years, and

was the music of the Mexican War, the California Gold Rush, and the Civil War.

The banjo was the foundation of the minstrel

show, and was always played with the back of the fingernail in the "stroke" or "banjo" style. The banjo went to California

with the forty-niners and out west with the cowboys. After the Civil War, soldiers returning to the mountains brought the

banjo and minstrel music back with them where it was preserved. Many of our present day songs such as, Angelina Baker, Lynchburg

Town, Gwine Back to Dixie, Ring, Ring De Banjo, Darling Nelly Grey, Hand Me Down My Walking Cane, Listen to The Mocking Bird,

Yellow Rose of Texas, Arkansas Traveler, Nelly Bly, Old Uncle Ned, to name a few, had their beginning in the minstrel show.

At the time of the Civil War, or as

it is referred to in the South: "The War of Southern Independence", The War Between The States", or "The War of Northern Aggression",

the banjo and fiddle were the most popular instruments of both player and listener. The popular minstrel scene with all of

its musical and political satire had been the pop music of the day for a almost twenty years. Every kids dream was to learn

the banjo, fiddle or bones and run off with the traveling minstrel show, and many of them did. It was only natural when

the war broke out and the call to arms on both sides was answered, there were literally thousands of banjo pickers, fiddlers,

and bones players joining up, both professional and amateurs.

To illustrate this point, there is

an interesting story by a Mr. A. Baur in his series of articles called "Reminiscences of a Banjo Player", published in the

February, 1893, issue of S.S. Stewarts "Banjo and Guitar Journal". Baur had learned the banjo as a boy in the early 1850s

and had joined the Union army early in the war. He writes "...In 1864 there very few regiments in the service that had more

than one wagon for the whole regiment... Strict orders were at all times issued that no baggage must be carried for an enlisted

man in any of the wagons...Where theres a will, theres a way, and a few of us managed with the help of a friendly teamster

to stow away a tackhead banjo and an accordion...

If the weather was pleasant a crowd

would gather around the camp fire, the banjo and accordion having been sneaked out of the wagon and a door from some farm

house or a couple of boards having been put on the ground on one side of the fire, the audience would take its place on the

opposite side, when the evenings entertainment would be gone through with. It consisted of songs with banjo and accordion

accompaniment, stories of home and jig dancing. The performances were crude but helped while away many a lonely hour and remind

us of home and friends in the far north.

Owing to poor facilities for keeping

the instruments in order, the instrumental part of our entertainments were always the poorest. Sometimes it would be weeks

before we could get a (banjo) string, and if the banjo head was broken, it took much time and maneuvering for one of our party

to steal into the tent of a drummer and punch a hole in a drum (head) near the shell, after which we would watch that drummers

tent with eagle eyes until he took the damaged head and threw it out, when one of the gang would pounce on it and bring it

to camp in a round about way. Owing to their thickness, the drum heads did not make very good banjo heads, but they beat nothing

clear out of sight. In addition to the banjo and accordion, we had a set of beef bones and a sheet iron mess pan answered

for a tambourine. Taking into consideration our surrounding and the disadvantages under which we labored, we had some tolerably

good shows and at any rate satisfied our open air audiences..."

Every brigade had its own minstrel

show with commanders trading or commandeering the best talent for his band not to mention the thousands of banjos being player

by the fire every night. John Billings writes in his book, "The Unwritten Story of Army Life", published in 1889, "There was

probably not one regiment in the service that did not boast at least one violinist, one banjoist, and a bones player in its

ranks...and one or all of them could be heard in operation, either inside or in a company street, most any pleasant evening....The

usual medley of comic songs and negro melodies comprised the greater part of the entertainment, and, if the space admitted,

a jig or clog was stepped out on a hard tack box or other crude platform."

The most famous banjo player of the

war was Sam Sweeney who was an orderly for General J.E.B. Stuart, commander of the cavalry in the Army of Northern Virginia.

Sams fame was derived from his brother, Joel Sweeney, who is credited as the inventor of the five-string banjo and the music

there of. Sam Sweeneys only job during the war was to play banjo for the troops and General Stuart, his officers and guests.

The banjo would be frettless (no little

strips of metal crossing the fingerboard) with gut with friction tuners. The neck wider than a normal banjo being about two

inches wide where it joins the rim. A calfskin head and metal parts bare brass or steel with no nickel plating and the number

of hooks holding down the metal ring which tightens the head should be between six and twelve. The metal band might be painted.

It was quite common for the head to be installed on the rim with brass tacks. This is called a tackhead as referred to in

the story above. The advantage is that it is simple and light to carry. The disadvantage is there is no way to tighten the

head when it goes soft because of rain, dew, or high humidity. This makes the tone become thumpy and muddled. The only solution

to a soft head is to hold it over the campfire a few minutes. It will tighten up for about twenty minutes and give a more

brilliant tone.

|

| Jim Bollman Collection |

The story of the banjo itself is a heritage of America

and its people: from the black folk in bondage in the South to the forty-niners in the hills of California, from the top hat

and tailcoat of Broadway, to the cowboys driving cattle from Texas to Wyoming, from the fraternities of Harvard and Yale in

New England, to the cabin in the darkest hollow of the Appalachian Mountains, the banjo has been there, played by our people

when our history was being made. The 5-string banjo is our American Heritage.

We all associate the 5-string banjo with songs from

Oh! Susanna and Ring, Ring de Banjo, to Foggy Mountain Breakdown and The Beverly Hillbillies, but how did the banjo come to

be our American heritage? The natural sound of the banjo is happy, joyous and exciting, but how did the banjo evolve? The

banjo has had a big part in performing the popular music of the American people for two hundred years. It has developed from

the simple round stick attached through a turtle shell with a groundhog hide and three horsehair strings into the "bluegrass

powerhouse" that, as Little Roy Lewis says, "...will peel bark off a tree".

Almost all ancient societies have had some sort of instrument

with a vellum stretched over a hollow chamber with string vibrations creating tones, but most research indicates that our

American banjo was developed from an instrument the Africans played here which they called banzas, banjars, banias, bangoes.

Africans, brought to the new world in bondage and not allowed to play drums, started making their banjars and banzas from

a calabash gourd. With the top one third of the gourd cut off, they would cover the hole with a ground hog hide, a goat skin,

or sometimes a cat skin. These skins were usually secured with copper tacks or nails. The attached wooden neck was fretless

and usually held three or four strings. Some of the first strings used were made of horsehair from the tail, twisted and waxed

like a bowstring. Other strings used were made of gut, twine, a hemp fiber, or whatever else was available.

To Americans of European descent, the banjo was a creation

of the Africans. The instrument was an oddity and was denied respectability. It was, in fact, a musical outcast, lowlier than

the fiddle which many "righteous people" knew was from the devil. According to a 1969 article in "The Iron Worker", a trade

publication of the Lynchburg Foundry Co. of Lynchburg, VA, a young man named Joel Walker Sweeney, of Appomattox Court House,

VA, learned to play a four- string gourd banjo at age 13, from the black men working on his father's farm. He also learned

to play the fiddle, sing, dance, and imitate animal sounds. Until this time, all performances on the banjo seem to have been

from black players. Joel started traveling through central Virginia in the early 1830's, playing his five-string banjo, singing,

reciting, and imitating animals during county court sessions. At this time he also started blackening his face with the ash

of burnt cork as was popular for performers to do. As he played his homemade banjo, which was probably made of a gourd, his

popularity and fame grew, so he enlarged his territory, playing in halls, taverns, schools and churches. These performances

seem to be the first time that the banjo had been performed in a show, and the novelty of his act charmed both Negro and white

spectators. He soon became a star in a circus which toured Virginia and North Carolina for several years. He eventually performed

on his banjo in New York City, and even toured England, Scotland, and Ireland performing for Queen Victoria in 1843. Sweeney's

introduction of the 5-string banjo to England led to the rise in popularity of the banjo there which has continued to the

present.

Facts are few and fables are many about Sweeney. One

such story has him playing the banjo with his toes, the violin with his hands, and blowing a mouth harp simultaneously. Later,

students of Sweeney showed that he had taught them to strike the string with the back of their fingernail and their thumb.

This is still the African way of playing. Today, a simplified version of this style of playing is called "clawhammer" or "frailing",

as well as many other regional names such as "knocking down", "old Kentucky knock", "thumb cockin", "rappin", "whammin", "flammin",

etc.

It is thought by some, that at an early age Sweeney

added the short thumb string to create the five-string banjo. Other evidence seems to indicate that Sweeney did not add the

thumb string, but rather added the bass string to create the five-string banjo. The entire time that Joel Sweeney was touring

and popularizing the five-string banjo, he was also teaching people to play it, among them, his brother Sam.

Around 1845 Joe Sweeney organized a minstrel troupe

called "Old Joes Minstrels", using his younger brothers Sam on the banjo and Dick on the bass. He also used his cousin Bob

Sweeney, a left handed fiddler, and some Negro dancers he knew from his area. Playing to thousands of people in their minstrel

shows they became an overnight sensation. Joel Sweeney died of "dropsy" at Appomattox on October 29, 1860, at the age of 50.

Sam Sweeney became the famous banjo player with General J.E.B. Stuart's headquarters staff in the Army of Northern Virginia.

Sam died January 13, 1864, of smallpox. Billy Whitlock, another famous banjoist who learned from Joel in 1838 while traveling

through Lynchburg, VA in a circus. He was the first to bring the banjo to New York City and was the talk of the town until

Sweeney came to New York City in 1843. Whitlock was the banjo player who, with Dan Emmett, formed the Virginia Minstrels in

1843 to start the minstrel craze. Whitlock also taught Tom Briggs to play Banjo. Briggs went on to be one of the leading banjoist

of the day and wrote the now famous, "Briggs Banjo Instructor". One other student was G. Swain Buckley, who became one of

the most proficient five-string banjo players of that time. Buckley was the first professional banjoist to perform in San

Francisco in 1852 with his family minstrel troupe, the famous Buckley's Serenaders.

The minstrel show had a very important part in the development

of the five-string banjo. As a result of Joel Sweeneys success in touring with his banjo and teaching so many to play, other

banjo players began to perform. The circus was a favorite venue for the banjo player, and minstrels carried the flavor of

the circus into their minstrel shows. In 1840, the now famous Dan Emmett, who later wrote Dixies Land, Jordan Is A Hard Road

to Travel, The Bluetail Fly, Old Dan Tucker , as well as many others, was working for the Cincinnati Circus Company as a drummer.

While touring through West Virginia in the spring, he found a banjo player by the name of Ferguson. Emmett wanted to learn

the banjo from Ferguson, so he persuaded the reluctant circus management to hire him. By the end of the 1840 season, Emmett

had learned to play, and Ferguson was a star in the circus on the banjo.

During the first minstrel shows with Dan Emmett on fiddle

and Billy Whitlock on banjo, as well as the shows put on by Joel Sweeney and his brother Sam, the audiences of minstrel music

were introduced to the sound of the fiddle and the banjo together as a complimentary duo. In his 1878 autobiography, Billy

Whitlock recalled that in Philadelphia in 1840, he played his banjo with a fiddler named Dick Myers. At that time, they performed

a show using the fiddle and banjo only. He claimed to remember this novel idea for later use. This sound is still popular

today in bluegrass and old-time music. Most people believe this is a sound from the mountains when, in fact, it was first

heard on stage in Philadelphia and New York City in the early 1840s, and even earlier by the black musicians on the plantations,

whose principal instruments were fiddle and banjo.

Emmett, Whitlock, and a few other boys were having an

old time jam session together in the North American Hotel in New York City, when it occurred to them they had discovered something.

As a result, they wrote a new chapter in Americas music tradition when they invented the minstrel show, using fiddle, banjo,

bones, and tambourine, with dancing. They called their act "The Virginia Minstrels", and opened on February 6, 1843, at the

Bowery Theater. They were an instant success, as they launched the minstrel show into the American heart for the next fifty

years. Due to the immense popularity of the Virginia Minstrels, the nation was beset with "minstrel mania", with hundreds

of professional and amateur minstrel troupes being formed over the next few years. The early bands usually consisted of banjo,

fiddle, bones, and tambourine. Other instruments were added, but a minstrel band had to have a banjo and bones to be legitimate.

Sometimes a band might have two or three banjos playing at the same time. As a result, hundreds of young men began learning

to play banjo.

As a result of hundreds of minstrel troupes traveling

by horse and wagon, stagecoach, train, and steamboat, the banjo was taken through the North, the South and out to the western

frontier. Mark Twain is quoted as saying about the first minstrel show to play Hannibal, Missouri, in the 1840s, " In our

village of Hannibal we had not heard of it (Negro Minstrelsy) before, and it burst upon us as a glad and stunning surprise".

In addition, banjo players still performed in the circus, many times as clowns. The "Mabies Brothers Circus", touring between

Wisconsin and Texas in the 1840s, used minstrel banjo players during the circus show, and afterwards performed a separate

minstrel show for an additional admission fee, thereby doubling their income.

"Steamboats a-comin" was a familiar call from the 1840s

through the 1890s. This was another major venue for the minstrel banjo player. Many minstrel troupes would work their way

up and down the river. The banjos influence moved all the way to the western frontier, wherever riverboats and circuses traveled.

Conversely, the four-string plectrum banjo players would have you to believe that the "Dixieland" style of banjo was played

on riverboats. This is not true. Because of historical evidence, we know that the minstrel 5-string banjo was played on riverboats.

Most of the riverboats were on the bottom of the river by the time the plectrum banjo was developed around 1910.

With the coming of the California Gold Rush in 1849,

the banjo moved to the far west. As it traveled around the Horn and across the continent it became the most prolific musical

instrument in the gold fields of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. In the Journals of Alfred Doten, he details how the clipper

ship he was on in 1849 stops for supplies in Valpariso, Chile. He and others, including a "darkey band" (minstrel troupe)

went a shore to have a party and serenade the senoritas with music from their banjos and fiddles. Doten, a banjo player himself,

wrote, "One song in particular is heard everywhere and it is the most popular song of any yet, it is Oh! Susanna." This song

by Stephen Foster became the anthem of the "forty niners" and took on a whole new set of words about the gold rush. Im sure

old Steve didnt mind. It was one of the first four songs he wrote along with "Uncle Ned" for his quartet. After all, E.P.

Christy had already cheated him out of it for five dollars and had assigned his own name to it as the writer. The professional

minstrel troupes were close behind Doten to fill San Francisco and the gold fields with music. Despite the tours of professional

minstrels, most of the banjo picking was in the gold fields by the music-hungry miners. In his journals, Doten speaks of many

occasions where he plays banjo and fiddle all night.

The 1850s and 60s was the high water mark for the banjo

in the minstrel show. As a result the popularity of the instrument spread to every corner of the nation and the frontier and

even on to Australia. Banjo players competed for the opportunities to perform in the minstrel shows whether amateur or professional.

The minstrel troupes with the best banjo player always got the best bookings. The competition by banjo players was intense

and they became the heroes and dreams of young boys who literally ran away from home to join the minstrel show. The art of

playing the banjo naturally increased in complexity even beyond what we perform today in the clawhammer or frailing style.

As a result of all this competition it is only natural that someone should hold the first banjo contest. It was held in October,

1857 in a large hall in New York City. By all accounts it was a knock down, drag out contest with half the city in attendance,

or not being able to get in and all shouting for their favorite banjo player.

The afore mentioned Tom Briggs who had been taught by

Billy Whitlock was touted as the best banjo player of the day and traveled with the Christy Minstrels troupe to California

to perform in San Francisco. Their route took them across the Gulf of Mexico, across the Istmus of Panama and up the west

coast. Poor Tom caught the fever crossing the jungles of Panama and died shortly after arriving in port. As a result, his

friend James Buckley published his almost finished banjo tutor. We still use this first banjo instructor manual as a standard

in learning the minstrel style today.

|

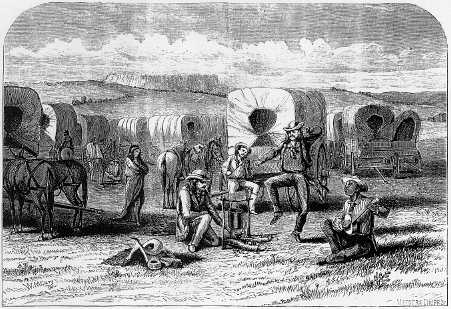

"The Train Encamped" by William

M. Cary

from Hearth and Home, Feb. 25, 1871, p.148 |

During the Civil War, thousands of banjo players joined

the army on both sides. As a result the banjo found its greatest growth as these banjo players taught others to play. A good

example of this is seen in the movie "Andersonville" where Martin, the banjo player teaches one the new prisoner to play.

(As a note of encouragement in learning to play, I built the two banjos used in this film and taught Ted Marcou who portrayed

Martin to play in in only eight hours.) Every brigade and sometimes companies had their minstrel shows every night not to

mention banjo players and fiddlers playing around the fire. A banjo was a prize find among the dead after a battle even if

the finder could not play. He usually knew someone who could.

Banjos and fiddles, being the popular musical instruments

of the day, moved west with the largest migration ever after the close of the war. Most of the men who became cowboys were

from the South, because of reconstruction causing a lack of jobs. Many freed slaves who could not find work also moved west

and became cowboys or "pony soldiers" in the United States Cavalry. Since music was such a major part of the recreation of

the soldiers and slaves, many brought their banjos and fiddles with them, strapped to their saddle horns, remembering the

songs they had known in the army or around the plantation.

The minstrel show, playing the popular music of the

day, continued to be the biggest influence on the popularity of the banjo, not only in the West, but in the entire nation,

as well as England and Australia. Of course, the most popular minstrel troupes, like Christys Minstrels, Buckleys Serenaders,

The Congo Melodists and The Virginia Minstrels, to name a few, remained on Broadway in New York and other big Eastern cities

where they reigned for fifty years. A few of them toured to San Francisco during the height of the Gold Rush, but they mostly

stayed where the money was in the east coast cities. Lesser known minstrel troupes had to travel to lesser known towns and

territories to make a living. Robert Webb points out that the minstrel bands were performing in Portland and Eugene, Oregon

as early as 1856, and very frequently after 1869. These minstrel troupes were common in all of the railhead towns in Kansas,

as well as the mining communities in Colorado and the Dakotas. Any town a cowboy might go that was large enough to have a

theater or a population with money, he most likely would encounter the antics and songs of the black-faced minstrels. These

minstrels bands traveled into the heartland of America, cris-crossing the continent, and playing in the desert Southwest regions

before the Mexican War.

Noted banjo picker and historian of cowboy lore in the

desert southwest, Greg Scott of Nogales, Arizona, told me, "Minstrel music was enormously popular in the mining camps and

towns throughout the West." Even as the number of touring companies in the East declined, minstrel troupes remained a mainstay

of entertainment in isolated farming, ranching and mining communities. Badger Clark, one of the earliest and finest cowboy

poets, worked for the Kendall brothers in Arizona Territory near Tombstone. In addition to the cattle ranch, the Kendalls

were noted semi-professional musicians who presented popular minstrel shows in Tombstone in the late 1800s".

In his book, "He Was Singing This Song", Jim Bob Tinsley

mentions the fact that some cattle drovers actually hired singers or groups of singers to take part in the cattle drives.

One such story involves a Kansas City cattle company by the name of Lang and Ryan who bought thirteen thousand head of cattle

from eastern Oregon in 1882. To help keep the cattle quiet at night they hired an entire band of Negro minstrels to sing to

the cattle on the long drive eastward to market. The term "Negro minstrel" does not mean they were Negros although they could

have been. Minstrel bands were referred to as "Negro Minstrels", or "Darkey Bands", because they "blacked-up" their faces

with burnt cork to appear as Negros. This band mentioned was probably either an eastern band stuck in Oregon and trying to

get back East or a western band traveling East to try to make it in the big time. This story is a good illustration of the

banjos presence on cattle drives, and the movement of the minstrels and their influence on the cowboys.

Don Blaylock of Cody, Wyoming, said his grandfather,

Frank Casner along with his brothers, Jess, Porter and Claude, were all working cowboys. They all played banjo, fiddle and

harmonica also. Frank, along with two of his brothers and his father, started out from Mills County, Texas in 1893, with eleven

hundred head of cattle for the Indian reservation around Fort Benton, Montana. With his banjo thrown in the chuck wagon, Don

said his grandfather played the banjo and sang from his horse while night herding around the cattle. From Ft. Benton they

traveled to Corvallis, Oregon to drive another herd to their home range in Datil, New Mexico.

Somewhere, sometime, probably in the 1850s, some guitar

player probably wanted to play banjo without learning to play the stroke style with the back of the fingernail. Apparently,

he learned to pick the banjo European style with the thumb and the fingers picking up just as the guitar was picked. As a

result, Frank Converse, a noted minstrel banjoist and technician, started perfecting this style and introduced it in his 1865

banjo instructor book. Together with another instruction book published in 1868 by previously noted minstrel banjoist James

Buckley, the finger-picking style was taught and developed. Consequently, at the end of the Civil War there occurred a split

in the playing style of the 5-string banjo. While the soldiers returning from the War brought back the banjo and the knowledge

to play it, to the seclusion of the Appalachian Mountains and to the far West, people living in areas outside the mountains

started turning to finger-picking, as a result of the availability of these banjo instruction books. The people of the mountains

and far West were generally too isolated to acquire these books, and continued to play a simplified version of the stroke

style on fretless banjos for their dances. Even though the stroke style persisted in the cities on the minstrel stage, it

had mostly died out by the turn of the century. Again, because of their isolation, the cowboys, miners, and professional performers

of the West also were slow in turning to the finger-picking style.

As a result of the finger-picking guitar style of playing,

the banjo in the cities and outside the Appalachian Mountain region started moving away from the "crass" minstrel music to

the more sophisticated classical style of music. Even though the guitar had been fretted since long before the development

of the banjo, the banjo had always been, with few exceptions, fretless from the beginning. In the 1870s strips of wood or

bone were installed flush in the fingerboards to represent where frets would be for those who were finger-picking up the neck

in the higher positions. In his 1860s banjo tutor, "Buckleys New Banjo Book", Buckley describes how to install frets in a

fingerboard and then notes, "The wire, made expressly for frets, can be obtained only of the publishers of this book". Around

1880, the first one to manufacturer banjos with frets was Henry Dobson, a famous banjoist from New York City and one of the

famous Dobson brothers who were all involved in making or playing banjos. The idea of adding frets was to increase the accuracy

of the notes when playing up the neck. Of course, the old stroke style banjo players shunned the frets as being unnecessary.

As finger-picking became more sophisticated in the 1880s,

there was a definite effort to "legitimize" the banjo and make it a classical instrument like the violin of Europe. The feeling

was that the banjo was a "feeble instrument", not able to be used in all keys and capable of only one, or at the most, two

scales of music. As the banjo started to move in this direction, outside the mountains, it moved into high society and more

ladies started to play. The new finger-picking style resulted in a change in banjo design from the deep, sonorous tone of

the minstrel banjo, with its large twelve inch plus head, to a smaller diameter head, with the designs incorporating metal

into the rims, tone-rings, and even casting the entire rim of metal. Outside of the famous S.S. Stewart banjos made in Philadelphia,

and the Buckbee banjos made in New York, most of the new generation of banjos made in the 1880s and 1890s were made by ten

or so banjo companies in the Boston area. The famous "Electric" and "Whyte Laydie" banjos built in the 1890s by the A.C. Fairbanks

Co., that are so popular with todays clawhammer players, were actually designed for finger-picking. Their design was to satisfy

the need for volume and tone with gut strings and a calfskin head.

In the 1880s and 90s, entertainment was not available

in the home as it is today, so it was common to belong to a social club. These were clubs that would bring people together

around a common interest such as poetry, railroads, rowing (boats), bicycling, theater, science and the like. At this time,

there were countless numbers of banjo clubs all over the country and in the leading universities and colleges, all of which

had their own banjo orchestras. Many of the clubs also presented banjo concerts hosting some of the leading banjoists of the

day. The socially elite thought it fashionable to play banjo in these orchestras. The music consisted of anything from classical

to marches to waltzes to rags and more. These orchestras were made up of the banjeaurine, a five-string banjo with a short

neck and a 12 or 13 inch diameter rim. Tuned a fourth higher than a regular banjo, it played the lead. Next was the piccolo

banjo with an 8 or 9 inch diameter rim and a short neck tuned an octave above a regular banjo. Although it looked like a miniature

banjo for a child, it was used in the orchestra for the tenor harmony. The regular banjo was used for the baritone harmony.

Many bands had a cello banjo with a 15 or 16 inch diameter head for the bass harmony. Sometimes guitars or mandolins were

included to round out the sound. Also popular for the parlor was the "mandoline-banjo" built by August Pollmann of New York.

It was simply a five-string banjo neck on a flat back mandolin body. Played like a banjo, it had a mellow, ringing mandolin

tone.

In addition to these banjo orchestra concerts and the

still popular minstrel show, there were some of the great banjo artists of the day that performed solo concerts unassisted,

such as Alfred A. Farland, Fred Van Eps, Vess Ossman, and Fred Bacon. Imagine a lone banjoist in concert on a stage playing

a banjo with a calfskin head and gut strings with no resonator and no amplification to an audience of 200 to 500 people. Some

of these virtuosos performed concertos by Beethoven, Paganini, and Mendelssohn and would use piano accompaniment. Attempting

this class of music for the student only exposed the limitations of the banjo and was discouraging. The flood of new popular

music written for piano was in C notation and the lack of the banjo's technical characteristics helped this style of banjo

playing suffer decline. In addition, the introduction of steel strings did not lend itself to finger-picking and the new jazz

dance bands found popularity with the public.

|

| Jim Bollman Collection |

In conclusion, evidence indicates that the clawhammer

or frailing style of banjo that we hear today is a direct descendant of the style taught to Joel Sweeney by black banjo players

in the 1820s. In the isolation of the Appalachian Mountains, as well as scattered individuals around the country, the old

stroke style continued unchanged in anonymity through the years. In the same way, I think there is no argument that the bluegrass

or three finger style banjo picking is also a direct descendant of the guitar style developed by Frank Converse, James Buckley,

and others during the time of the Civil War.

Yes, the five-string banjo is our American heritage.

As was stated, the banjo has been present through Americas history and has had a big part in performing the popular music

of the American people for over two hundred years. The next time you are at a concert or a festival and hear that hot banjo

break, remember, you are hearing the continuation of a two hundred year old story.

Many thanks to Bob Flescher for his information on

the history of minstrel music and the banjo.

|